What Happens When You Slow Down Enough To Ask Questions?

Questioning an end-of-school tradition felt like breaking the rules; maybe that’s the point.

Hi Friends,

A green sheet of paper haunted me for a few days last month. It was one of those innocuous end-of-school-year forms, the kind that are best if you fill out without thinking too much about them. Except I did.

The form was innocent enough, asking me to order a t-shirt for Field Day. For the uninitiated, Field Day is a day schools hold towards the end of the school year, where students participate in various physical activities such as tug-of-war, water balloon fights, and relay races. Why? I could give you some lines about how it's designed to promote teamwork, exercise, but really, it's the end of the year, and everyone is exhausted and stir-crazy.

One thing you should know about me is that it's rare for me to see anything and accept it as status quo. I'm always looking for ways to make things, big or small, just a little bit more sustainable. Clearly, right? I mean, a lot of people see the issue of climate change as a problem but wonder what they can really do about it, and I spent nearly 4 years researching and writing a book on what, if anything, parents and kids can do about climate change. My brain isn't wired to think a problem is too big to solve or that just because we've always done something one way means we should keep doing it. As you subscribed to this newsletter, I'm guessing you are wired somewhat similarly or at least curious about that way of thinking.

When I saw the form and noticed that my kid's grade level was supposed to order yellow shirts, I thought fine. The school wants them to easily tell which grade is where during what I can only imagine is a chaotic day. I figured instead of buying a t-shirt, my kid, who will never wear this shirt again (She's not a t-shirt fan), would wear a camp shirt that is also yellow. Or I would ask the older, wiser kids at the bus stop if they happened to have one of theirs she could wear.

But then my kid said she was pretty sure the shirts were mandatory. This was curious. My kid goes to a public school, and it’s a great school, yet still, mandatory anything is rare. I emailed the school to confirm and was informed that whether or not I purchased a shirt, my kid would receive one. I was now fascinated.

I love research, so I started a list of all the questions I had about these Field Day T-shirts.

Assuming my child spends all six years in this particular school and they have Field Day and the Field Day T-shirts each year, could I determine the carbon emissions of my kid's t-shirts?

What about the carbon emissions of the production of the t-shirts for the entire school over the same period?

How long has this been the school policy? Could I determine the carbon emissions of the entire production?

What about the carbon emissions of the life cycle of the t-shirts? This would likely be harder, if not impossible, on the school-wide scale as the emissions are lower the longer you use the t-shirt, so my kid who will wear this t-shirt once will have a higher impact than someone who uses the shirt far more.

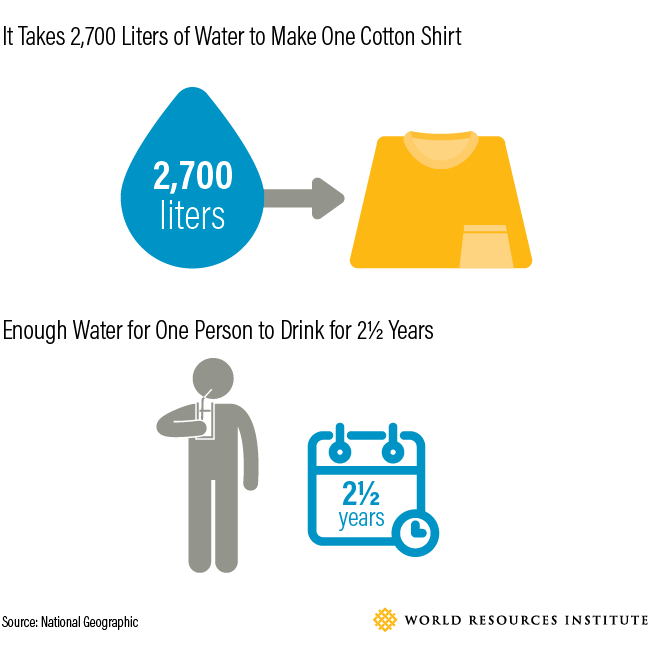

This, of course, brought up another question. What were the t-shirts made of? Making a cotton t-shirt requires hundreds of gallons of water, estimated to be enough drinking water for one person to live on for 2.5 years. Then there are the synthetic materials; t-shirts made of for instance polyester, can release microfibers every time they are washed. In an average wash load, one study found that up to 700,000 microfibers are released. These are essentially microscopic pieces of plastic that end up in the soil, waterways, marine animals and us. Maybe it was a good thing my kid would never need me to wash this shirt.

Why was there not some sort of recycling program in place? Washing synthetic material aside, the longer you use a shirt, the lower the overall environmental impact. Why couldn't classes have one color that stayed with them throughout elementary school? Yes, some people would need to buy more than one shirt in that period; kids grow, and things get lost, but you could get away with less overall. Less than 500 kids are in this school, and the parent population is very involved, so much so that signups for Field Day volunteers are a timed event with spots scooped up very quickly. It seemed not unreasonable that another option for the shirts was for five parents to be responsible for collecting 100 shirts at the end of Field Day, washing, sorting, and storing them for next year. Or 10 parents could each be in charge of 50. Again, some shirts would still need to be purchased likely each year, but less.

And then, finally, is it impossible for us to have a day of joy without turning it into something commercial? This day and the once-a-year new t-shirt was also a lesson in consumerism. Make no mistake, along with the math, writing, and reading, school is about teaching kids to be good little Americans, and that means buy buy buy. Consume our way to extinction while giving the billionaires ever more resources to plot their escape to space.

The form continued to sit on our entranceway table. My kid asked about the cost. $8 isn't a lot for a t-shirt. Is that good? I don't know. Maybe the school is helping to pay for their cost, but there likely isn't much good about an $8 t-shirt. It's almost impossible to make a t-shirt and sell it at that price that isn't harming either the people making it, the planet, or both, I replied. I added: is the school subsidizing the t-shirts, and where are they being made to my list of questions.

I went back to my kid's school to inquire a bit more about the Field Day T-shirts and, this time, received a phone call explaining that this would be the 9th year they have mandated the t-shirts and that it was not possible to do any recycling. I pushed back on that. Not for this year; I'm not an insane person, and there isn't enough time, but couldn't we figure out a more sustainable solution for next year? I'd be happy to help. At this point, it was clear I had hit a nerve and was not the first to ask at least some of these questions. I was given a line about the impact being up to each individual caregiver that felt straight out of the Big Soda playbook: the plastic bottles aren't the problem; the problem is you're not recycling. I was told Field Day was about inclusivity and joy. I was being asked to conform to the rules, but I believe that to live in this world that is growing ever hotter and to raise kids who can live in it requires us to think deeply, to problem solve, to ask questions, and to adapt. To consider our impacts on the planet and people.

I reached out to the company listed as manufacturing the t-shirts to ask a few questions about their processes. I got a quick reply from the CEO, who explained that while they would love to manufacture all in North America due to labor costs, they primarily made the t-shirts in Nicaragua, Honduras, and Mexico. By this time, I had confirmed with the school that they were paying for the shipping of the shirts but were not otherwise subsidizing their cost. I didn't ask the CEO if they were using Fair Trade manufacturing facilities or if the factories were third-party audited in any way. They could be. Those places exist. But those countries are also known for a garment industry where, in some cases, child labor is used and where women, mostly from low-income areas, are subjected to all sorts of abuse while making inexpensive clothing. This isn’t an issue unique to those countries, but so-called fast fashion in general.

It's a luxury to be able to think of these questions and to ask them. Our systems are set up to make our daily lives so busy that we don't have time to think or ask questions. Mostly, all we have time to do is go along with the systems already in place, and that's done by design. Start thinking too much about something that should be a simple, fun, end-of-year day, and you either want to scream about how messed up our society is or throw up your hands and say we're doomed—or both.

The school, I decided, was giving me a gift. At this point, on an individual and community level, the climate crisis is ultimately about values. What do you stand for, and how do you stand for it in a system set up to almost always make you compromise your values. The school was asking me if I wanted to help fund something that I saw as unnecessary and harmful. They were giving me the option to say no with little consequence (my kid was going to get a shirt either way). It was an incredibly rare choice to have, but it was an easy one to make.

My child, in all likelihood, will spend another 5 years in that school, and each year, I will likely be asked to pay for a Field Day T-shirt, and I will keep asking if there is a better way. Will it make a difference? Probably not. Maybe I'll get a few more parents to go along with not buying the shirts each year. Maybe if enough people don't buy the shirts, the school will be forced to think of a different option. I think this is doubtful. But at least in this one small instance, I didn't have to help the school fund something I decided was ultimately causing more harm than joy. I got to live my values.

Of course, it’s not really about a t-shirt. It’s about slowing down enough to question why things are done the way they are and whether they align with the values I want to live by. It's easy to fall into the trap of accepting "this is how we've always done it" and move on without thinking. But maybe by questioning what we accept as "normal," we can create new ways of doing things that not only serve us better but also serve the planet.

~ Bridget